Familiarity

The Narrative that Boarders the Known and Unknown

“Why did they make birds so delicate and fine as the sea swallows when the ocean can be so cruel”

- Earnest Hemingway, The Old Man and the Sea

Confronting the Unknown

Venturing over 32 hours by plane and hours more through bumpy dirt roads that wound around terraced mountains like jungle pythons, a 12-year-old version of myself breathed humid Ugandan air. I intimately encountered a foreign world within my lungs lightyears from the cozy suburbia of Denver, Colorado.

Staying for a time around Lake Bunyonyi, the group that my family and I had traveled with was on a path to establish life-changing and perspective-challenging relationships with the people of the region. This meant diving head first into communities and their many members and meeting them where they stood. By no means were we on any sort of mission trip; if anything, we were on a vision trip.

As part of this search of vision, I brought a camera.

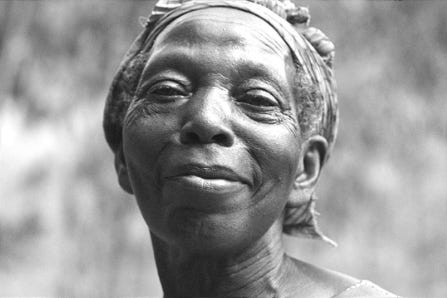

This portrait above was taken by myself while in one of the villages that surrounded the mountainous region Lake Bunyonyi is nested within. Its subject remains unknown, but rather than discussing the subject in isolation, I want to talk about the depth of interaction that coincided with the taking of this photo.

Mini Muzungu

As the only kid on this trip; I was often the first child with fair complexion that many within Uganda had seen, this was often met with fascination and curiosity; I was the mini muzungu.

The word muzungu originates from Swahili, used to describe the first white individuals who arrived in East Africa. This is presently used throughout the continent and is common to describe travelers and tourists, but its true meaning is wanderer.

I was a wanderer in the truest sense of the word. Aimless, I was submerged in a foreign land and was met with peoples fascination everywhere I went. Firstly, because I was American, secondly, because they were African, tertiarily, because we were both human.

Kids approached me and touched my skin and hair everywhere we went, viscerally experiencing this paradigm shift of my unfamiliar complexation juxtaposed with the ordinary silhouette and proportions we shared. This child is one of those children fascinated with the mini muzungu who embodied the familiar and unfamiliar all at once.

Confronting the Familiar

Our minds live within perpetual juxtaposition. Neurologically, our brains are continuously trying to leave unnecessary information by the wayside, yet, our curiosity propels us to seek out that which is unknown. This seemingly contradictory state is the force that borders the familiar and unfamiliar, causing expansion and deflation of such bodies of knowledge and ignorance.

If our minds are a blazing campfire, our narratives contrived from limited and continual pursuits of understanding are the burning light that flickers over the surrounding trees; dark in many places, illumined in a few, always flickering and changing.

I use the word narrative here intentionally, because we live our lives through story; a thread which weaves a variety of information and data into broader cohesive understandings.

Take any myth, secularly seen as bygone folktales, is a constellation that communicates wisdom and knowledge, bridging perspective and expanding the illumination of our campfire. In Uganda, the cultural tale of the muzungu stood as a bridge through which my ongoing story and their ongoing story could intersect, expanding both to an equal degree and allowing one to become apart of another.

Our stories are not only vague boundaries which surround our knowledge and experience, but ways in which our stories can expand and become incorporated with the stories of others. Stories that both discern and link, distinguish and connect our vision.

Frames within Image

And as part of this search of vision, I brought a camera.

With this camera, I can only see to the border of its lens. The contents of its frame is my story. Others around me have their lens, often with completely unique contents. However, once in a great while, I and another will share a subject in our frames. This common ground makes our frames no longer frames in themselves but frames of the same image, experiences of the same story.

In a village nearing Lake Bunyonyi leagues from home, this very thing happened with the residence of the village and the mini muzungu. We each had our individual frames, our stories and experience, yet our shared humanity was the image that united these frames taken from other worlds, bringing them to be one.